Log: Stopping at Marketing

After Apple introduced Log format video recording capabilities on the iPhone, Android brands were naturally quick to follow suit, each launching their own Log video format. Looking at their implementations and practices, some manufacturers provide relatively clear documentation and tools, while others lack even specification sheets. More often than not, it stops at being a line in a launch event or an advertisement. From my anecdotal evidence, the number of people actually using Log on Android phones is vanishingly small, you could count them on one hand.

Log is something that heavily relies on ecosystem and toolchain support. After all, Log video is created for grading, not for direct viewing. The essential parts of using Log are correctly recovering information from it, integrating it into a workflow, and finally producing a video for the audience, not just applying a tonal compression during capture.

On this point, we must invite Apple, the pioneer of phone Log, for comparison. In popular software like DaVinci Resolve, you can directly use LUTs made for Apple Log, or select Apple Log and Apple Wide Gamut directly as input transforms in the Colour Space Transform (CST). Furthermore, with automatic colour management enabled, Apple Log footage can be directly recognised and managed automatically. Footage shot on an iPhone and footage shot on a camera can collaborate seamlessly, with no difference in the user experience.

The situation on the Android side is rather poor. As of November 2025, VIVO has not released a specific whitepaper. OPPO provides a whitepaper detailing the specifications of OPPO Log and OPPO Wide Gamut, along with LUTs for conversion to SDR (Rec. 709) or HDR (PQ), as well as CTL and ACES code. Xiaomi’s situation is similar to OPPO’s, and they supported it earlier; the colour science library colour-science has already added support for Mi-Log.

It’s worth mentioning that the experience of shooting Log on an OPPO phone is quite poor. First, you need a Find X8 Ultra or a later Find series phone, or a OnePlus 15. Then, you need to navigate to the secondary menu for ‘Pro Video’, and click on settings to find the Log option. After enabling it, you can only judge exposure using a very crude histogram, and there’s no monitoring LUT. ISO needs to be greater than 800, but you can manually select lower values. In this case, the signal is stretched (similar to extended ISO), resulting in a loss of dynamic range, with no warning given. After shooting, there is no way to apply a viewing/recovery LUT in the gallery app, making it impossible to edit and share directly on the device.

OPPO phones before the X8 Ultra also have a Log video option in the same location, but the footage recorded is not OPPO Log and cannot be correctly restored using the corresponding curve or LUT for OPPO Log, rendering that Log feature completely unusable.

To be blunt, Log video on Android currently has no real user base, lacks third-party software support, and has not formed a community ecosystem. It remains a marketing gimmick.

OPPO Log

Although it’s essentially unusable, since it exists, let’s take a closer look.

To understand OPPO Log, the best choice is naturally its whitepaper. The whitepaper is available in both Chinese and English, with some differences in content, so they can be used as references for each other.

From the whitepaper, we learn that the video uses H.265 4:2:0 10bit encoding, with a bitrate of 120 Mbps for 4K 60fps. Shooting one minute of 4K 30fps requires 600MB, and one minute of 4K 60fps requires 900MB, which is quite substantial.

OPPO Log is a scene-referred logarithmic colour space, composed of the O-Log curve and O-Gamut. The O-Gamut is consistent with ITU-R BT.2020, which is also the choice for Mi-Log.

The form of the O-Log encoding/decoding function is simple. The encoding curve is:

$$ P=f(R)=\gamma*\log_{e}(R+\beta)+\delta $$Where the reflectance R ranges from 0-1600%, $\gamma$ = 0.139, $\beta$ = 0.019, $\delta$ = 0.614, and the approximate value of the natural logarithm base e is 2.7182818. The resulting normalised floating-point value is stretched to 0-1023 to obtain the code value.

This curve has about 6.47 stops above mid-grey. Calculating from the minimum luminance change, there are roughly another 10 stops below mid-grey, making it a Log curve with strong carrying capacity. The following chart uses Exposure Value (EV) as the horizontal axis, normalised to mid-grey.

The corresponding inverse function is the decoding curve:

$$ R = f^{-1}(P) = e^{\frac{P - \delta}{\gamma}} - \beta $$Where the normalised floating-point value P ranges from 0.0631271 to 1.

A rather odd point is that, according to the formula or CTL code in the whitepaper, it’s impossible to calculate the example values in Table 1 of the whitepaper. Particularly for 18% and 39% reflectance, there are differences starting from the second decimal place of the normalised floating-point number. Additionally, the normalised floating-point numbers in the table cannot be accurately converted into the 10-bit code values listed in the same table, requiring further investigation.

Restoration LUTs

OPPO provides two restoration LUTs: one for SDR to Rec.709 primaries with Gamma 2.4, and one for HDR to Rec.2020 primaries with PQ 1000 nits. The precision is 65 steps.

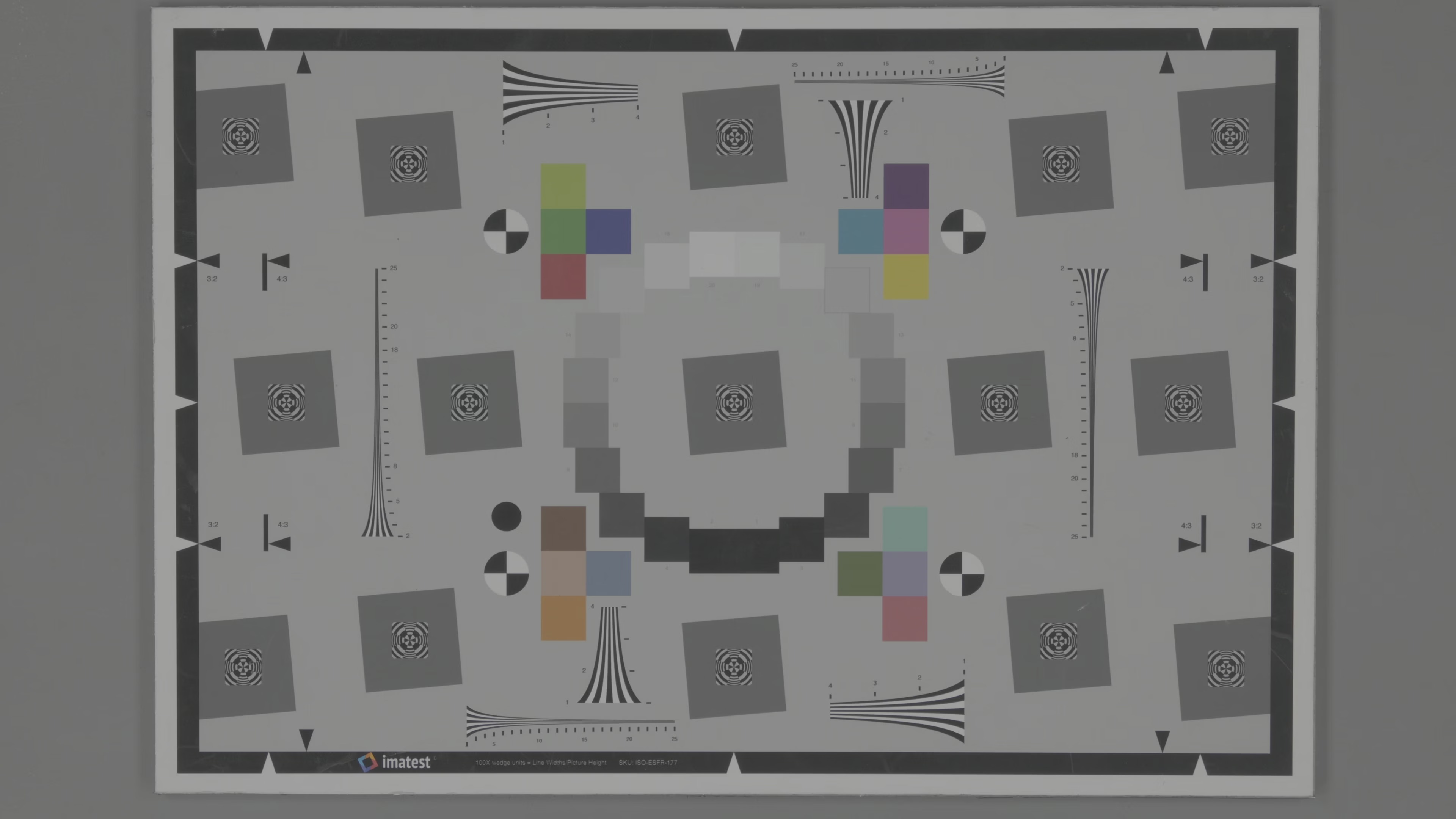

This is an evenly lit Imatest chart, a screenshot from an OPPO Log video.

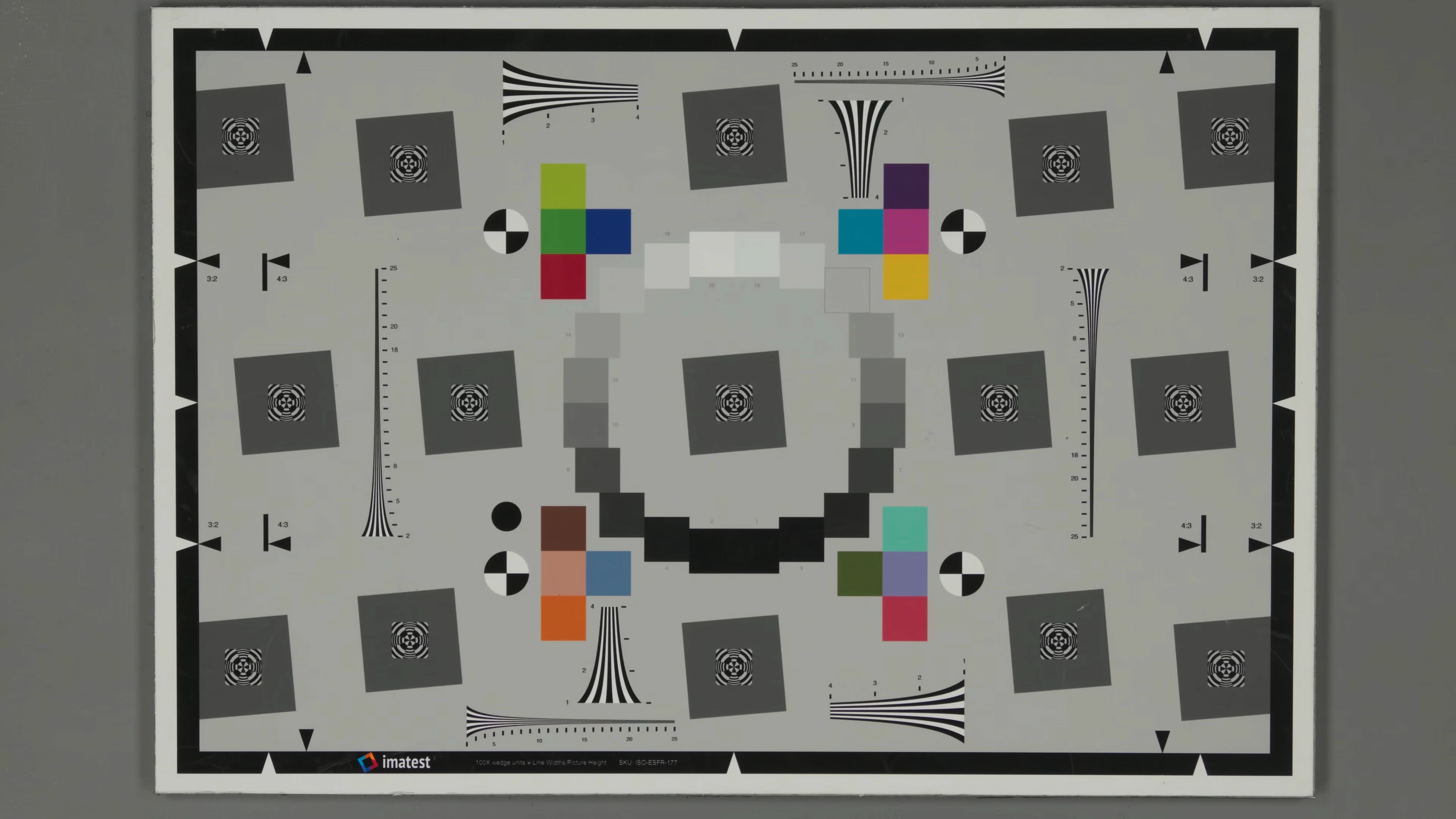

This is how it looks after applying the SDR LUT. It’s noticeable that the video in Log mode has almost no sharpening applied, and the colours are relatively natural, appearing much cleaner than the highly sharpened, overly vibrant look of the phone’s default video mode.

This is a manually set up HDR scene, consisting of an evenly lit canvas with additional lighting at the sun’s position. At the sun’s position, you can vaguely see that OPPO Log has retained highlight information.

This is how it looks after applying the HDR LUT. This LUT is more stylised compared to the SDR one, with more vibrant colours, but it’s still significantly better than the HDR in the default video mode. PQ video is theoretically absolute luminance, but the image is normalised to 203 nits for display here, converting it to relative luminance. Therefore, it’s more appropriate to understand this image as having 2.3 EV of headroom.

Log: More Than Just Marketing

Collecting information, attempting to reproduce the values in the documentation, using LUTs and colour space transformation methods to output Log footage to a viewable result, each step in this process had its minor issues. Fortunately, a good final result was achievable. This at least shows that a Log workflow on a mobile phone is possible and can yield results superior to the phone’s default video mode.

Compared to still images, video has more specifications and requirements regarding containers, encapsulation, and standards, demanding a deeper understanding of the entire pipeline. Apple is far ahead, leading by a significant margin. But at least Android has taken the first step. In this fast-paced market, properly assessing the concrete value of Log and realising that value across the entire pipeline requires patience. If it remains just a line in a launch event script, that would be a real shame.