Hisense unveiled an RGB MiniLED TV with four primaries at CES 2026, adding a cyan emitter on top of the original set to deliver a wider colour gamut and “better visual health”. This post is a bit of a “no-hardware demo”: an analysis without having the TV in hand.

Clues in the Marketing Materials

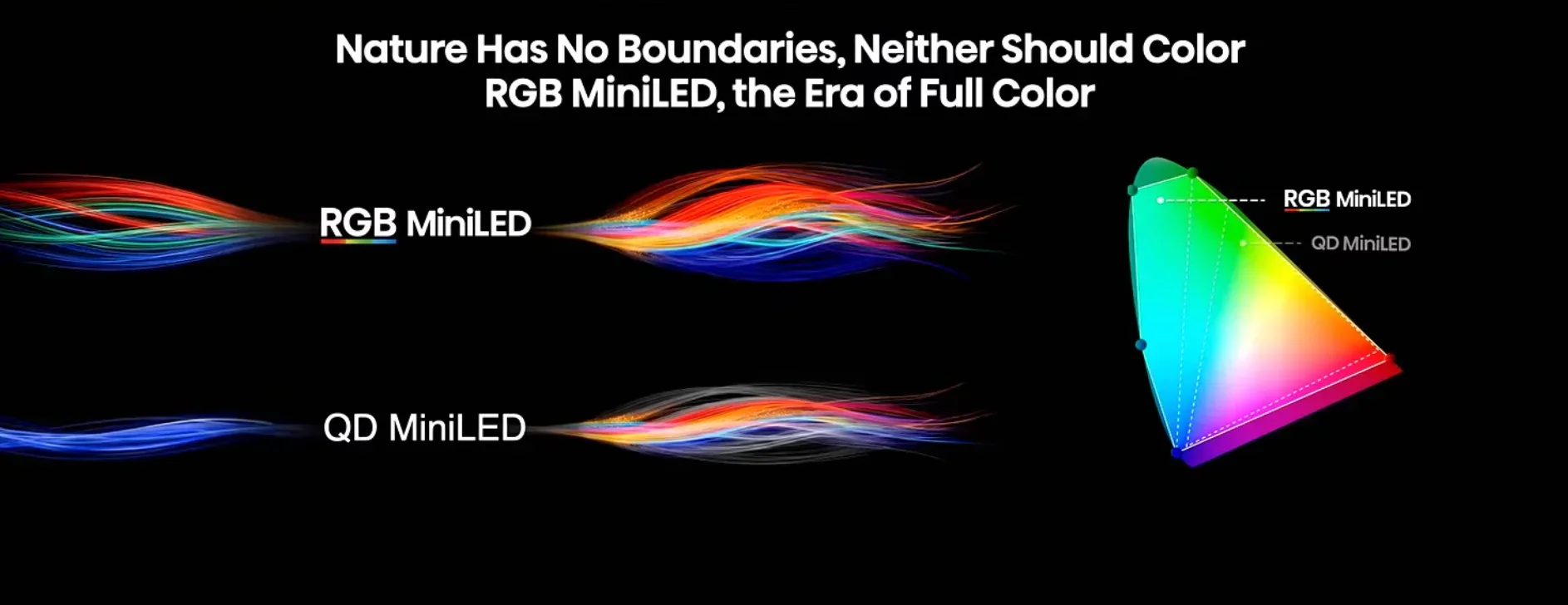

First off, this CIE 1931 xy chromaticity diagram for the RGB MiniLED already shows five primaries — the blue-green point in the upper-left might simply be drawn in by mistake. From this diagram you can see that, on the horseshoe-shaped CIE 1931 xy plot, trying to cover it with a triangular region puts you at a disadvantage when calculating coverage, but that doesn’t mean three primaries are bad; it’s more likely a limitation of the diagram.

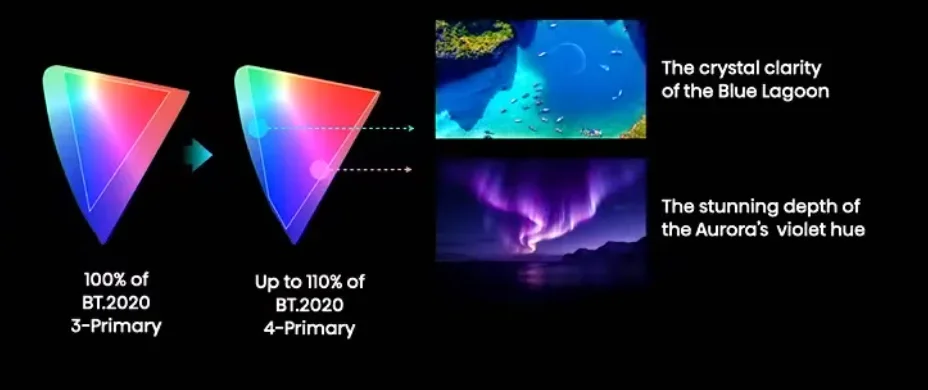

The coordinates in another set of images look more sensible and also match the wording in the press materials, so I’ll use that one for the analysis.

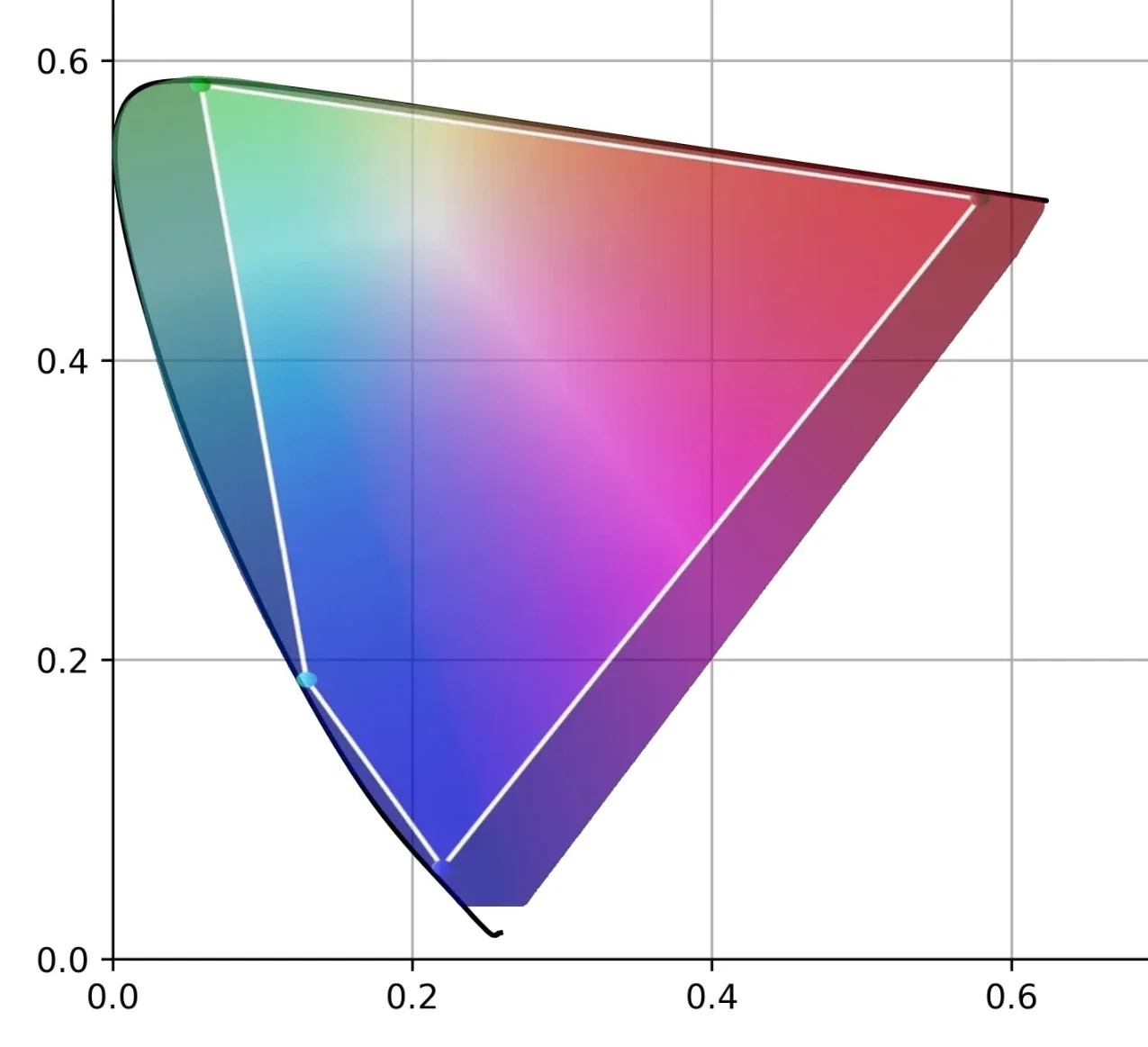

This chromaticity diagram looks like a stretched 1976 UCS. I overlaid a video screenshot with the spectral locus on CIE 1976 UCS in Photoshop to line them up, then did a rough read-off of chromaticity coordinates from pixel positions.

In the launch video, the animation that moves from three primaries to four takes the original blue coordinate and shifts it left and right into two points, and it repeatedly mentions a few blue-related properties. So the focus of this cyan-based multi-primary setup is probably that the “blue” part gets split into two primaries; red and green change less, aside from being closer to the spectral locus.

Based on the points I picked above, the blue chromaticity moves from (0.1991, 0.0878) to (0.2195, 0.0626), and the added cyan is (0.1282, 0.1873). The original blue sits roughly on the line between the new blue and cyan, a little closer to blue. If we infer dominant wavelengths, the old blue is around 456 nm, the new blue around 448 nm, the cyan around 473 nm, while red and green are about 531 and 639 nm.

Of course, my point-picking could be off, and Hisense may have only drawn a schematic. Everything that follows could be completely wrong, but the multi-primary discussion is still useful as a reference, especially around the two main claims this time: better visual health and a wider colour gamut.

Visual Health and Circadian Rhythm

This cyan LED is likely around 475 nm. Compared with the ~450 nm blue used in many displays, it has less short-wavelength content. The advert says “harmful blue light” is only 15%, 50% lower than QD-OLED and 75% lower than QD-MiniLED. That probably means a lot of what the original blue LED used to do is now handled by this cyan LED; the longer wavelength brings down the share counted as harmful, fitting the usual “hardware low blue light” claim.

When people talk about “blue-light hazards” from displays, it mostly comes down to two things: retinal damage and effects on circadian rhythm.

Retinal damage is still heavily debated. The idea is that high-energy, short-wavelength light can oxidise retinal cells, but some experiments suggest you need very intense exposure to cause meaningful harm; a screen simply doesn’t deliver enough dose to damage the retina. And the concern tends to focus on the shorter wavelengths around 415–455 nm. If you switch to a cyan LED, even though the new blue LED is shorter in wavelength than before, its power output should drop a lot, which naturally looks favourable when you calculate the proportion of this “blue” component.

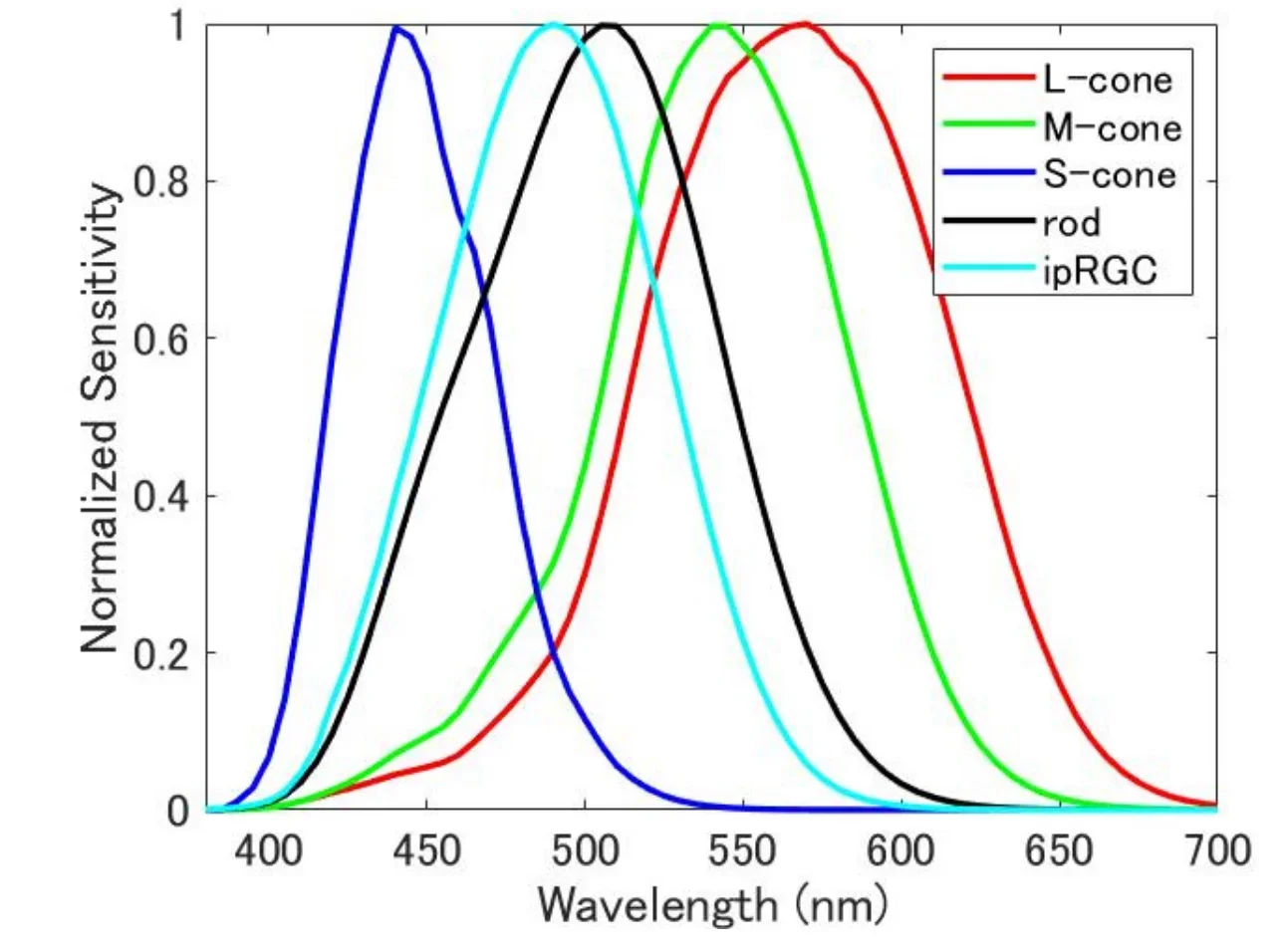

The other, better-evidenced effect is how displays influence circadian rhythm. The mechanism is stimulation of intrinsically photosensitive retinal ganglion cells (ipRGCs). These cells don’t contribute directly to vision, but they’ve been shown to regulate the suprachiasmatic nucleus in the hypothalamus, shaping human rhythms, for example by suppressing melatonin secretion. Melanopsin in ipRGCs is most sensitive to light around 480 nm, with a spectral sensitivity between the S- and M-cones. The new cyan LED’s peak wavelength and spectrum are likely to overlap strongly with the ipRGC response, so it may affect circadian rhythm more than the original blue light.

Image source: M. Ohtsu, A. Kurata, K. Hirai, M. Tanaka, and T. Horiuchi, “Evaluating the influence of ipRGCs on color discrimination,” J. Imaging, vol. 8, no. 6, p. 154, Jun. 2022, doi: 10.3390/jimaging8060154.

Ultra-Wide Colour Gamut

According to the marketing, the new four-primary system can reach up to 110% of BT.2020. Clearly that’s an area ratio, not coverage. With my rough digitising, on the CIE 1931 xy chromaticity diagram the four primaries reach a 107.2% area ratio and 98.03% coverage; judged by the more meaningful coverage figure, you could call it a BT.2020 display.

If you keep red and green unchanged, and use the original blue point, the area ratio is 99.1% and coverage is 93.9%, which roughly matches the previous-generation RGB MiniLED. Earlier I guessed the cyan LED might be doing most of the work, with the blue LED acting as a supplement, so if you only use RG-Cyan as a three-primary set you can still hit a 97.3% area ratio and 94.7% coverage. But change the blue primary from blue LED to cyan actually improves coverage? That’s really a CIE 1931 xy issue: the blue region is too compressed. Moving from blue to cyan looks like only a small step, yet it brings cyan closer to BT.2020’s blue primary, inflating the calculated coverage.

If we switch to the more uniform CIE 1976 UCS and recalculate coverage, RGB-Cyan comes out at 98.9%, the RGB set with the original blue at 93.1%, and the RG-Cyan set drops to 86.7%, closer to what you’d expect.

On CIE 1976 UCS, the new RGB-Cyan still achieves extremely high BT.2020 coverage, and most colours can be produced using just RG-Cyan, without involving that shorter-wavelength blue. The four-primary area ratio is a shocking 128.8%.

From CIE 1976 UCS you can see that shortening the blue wavelength pushes the blue primary down towards the lower-right, which helps both gamut area ratio and coverage calculations. In practical terms, it expands the gamut for magenta, purple and deep blues, Hisense’s example was the aurora. Seen this way, the ultra-wide gamut and very high area ratio owe more to that blue LED. It also reinforces that, for ultra-wide-gamut devices, you really shouldn’t be using the CIE 1931 xy diagram to compute coverage or area ratio.

Colour Mixing in Four-Primary Displays

With three-primary displays, colour mixing works like this: on a linear chromaticity diagram, a colour inside the triangle maps to a unique set of primary ratios at the triangle’s corners. But with four primaries or more, you get much more freedom when choosing the primary combination, in theory there are countless combinations that can mix to the same target colour.

That extra freedom needs stronger display driving and more complex algorithms, but it also gives you more room to tune things: beyond matching colour, you can add constraints. For example, if you want the mixed spectrum to have a lower ipRGC response to be kinder to circadian rhythms, the algorithm might bias against using the cyan LED. Or if you want less short-wavelength blue, it might lean harder on the cyan LED. It can also be used to improve issues like metamerism.

Another four-colour product announced at the same time adds a yellow primary. Yellow is very likely to sit on the line between red and green, so it contributes little to gamut, but using yellow and blue to make white might improve power efficiency, another multi-primary mixing strategy.

A simpler strategy is to split the four primaries into two groups, divide the polygon into two triangles, and treat them as two three-primary displays: first decide which triangle the target colour lies in, then route it straight to the three corresponding primary drivers. For this RGB-Cyan TV, one possible split is RG-Cyan and RB-Cyan: the former covers about 85% of the area, while the latter fills in aurora colours, magenta, and blue-violet. This approach is simpler and can reuse existing algorithms, but a downside could be colour jumps near the line between R and C, where you switch between two characterisation models.

For this four-primary product, there’s also a potential issue: the backlight uses four-colour LEDs, but the colour filter layer up front still looks like three. Coordinating backlight brightness and filter transmittance could be a big challenge, and you’d also have to think about zone-to-zone crosstalk and so on.