Translated from Chinese version by Gemini 3 Pro Preview.

Starting from Green Beans

Specialty coffee has long formed a complete industrial chain: from harvesting and processing at the origin upstream, to transporting green beans into the country, and finally, the roasters roasting them into finished beans for sale.

Once you’ve bought enough coffee beans, you start to notice that different roasters seem to be selling the exact same bean. A quick search online reveals that this is actually because they are all buying from the same green bean importer. Since that is the case, could I try roasting them myself?

These yellow-green things are green coffee beans; specifically, they are Hambela XS (known as ‘Huankui’ in China) from Hongshun Coffee, carrying a scent of herbs and grains. Some “raw coffee” products on the market (like certain drinks from Starbucks or Luckin Coffee’s “Light Coffee”) utilise green bean extract, which tastes distinctly grassy and is rich in chlorogenic acid. Such green beans are not suitable for direct grinding and brewing.

Coffee roasting is a complex and fascinating process of chemical and physical transformation. Essentially, under the influence of heat, green coffee beans undergo dehydration, the Maillard reaction, and caramelisation, transforming their internal compounds into flavour.

Therefore, roasting coffee beans requires a machine capable of transferring heat to the green beans, for instance, in the form of hot air, much like the protagonist of this article: the Matchbox H7S Lite.

The Matchbox H7S Lite

The reason I bought it was simply that it was cheap enough, and the companion software offers plenty of assistive functions.

It comes in very simple foam packaging. The accompanying power cable is 1.5mm², supporting the 1800W power needed to provide sufficient thermal energy.

The compact body made of aluminium alloy was also a major reason for my choice.

The product name “Matchbox” is engraved on the side; the brand feels somewhat akin to a small workshop operation.

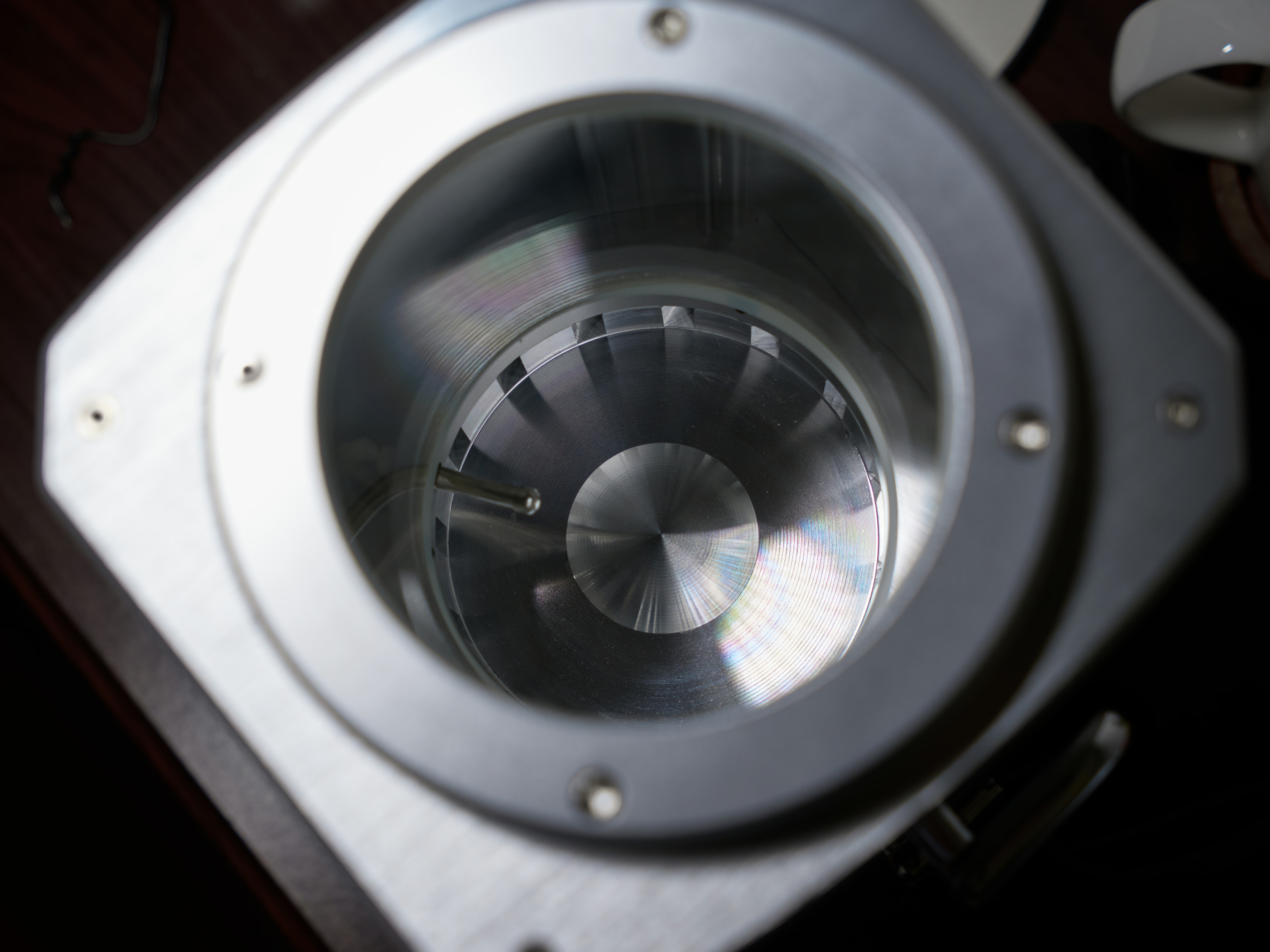

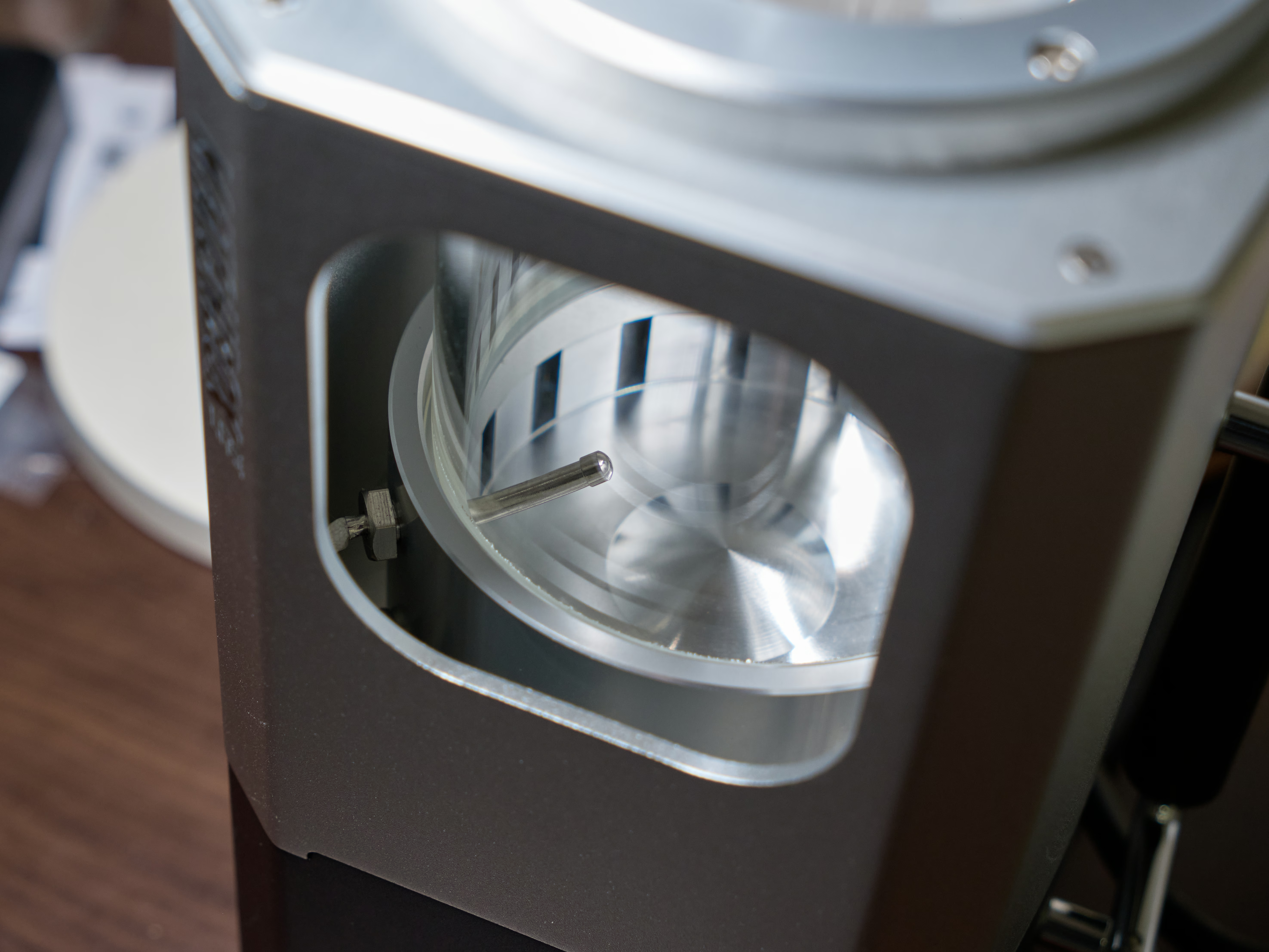

Removing the chaff collector at the top reveals the glass tube which acts as the bean hopper. Below it is the hot air outlet, where spiraling air blows the coffee beans in a rotation to ensure even heating.

The protruding object is a temperature sensor used to detect bean temperature and monitor the roasting progress.

During the process, the coffee beans are agitated by hot air, gradually raising their temperature. The colour shifts from the yellow-green of the green bean to yellow as they dehydrate, followed by a series of chemical reactions turning them brown. Around 190 degrees Celsius, the internal pressure from water vapour and carbon dioxide causes the internal structure to rupture, producing a crisp cracking sound known as “First Crack”. Shortly after the first crack, the heating can be stopped to obtain light roast coffee beans.

During roasting, a thin film on the coffee bean peels off as the bean expands. This is called “chaff” (or silver skin), and these flake-like scraps are blown into the collector by the hot air.

Roasted Beans and the Pros & Cons of Home Roasting

Finally, we end up with the familiar roasted coffee beans. Having gone through dehydration and other stages, the weight of the roasted beans is about 10% lighter than the green beans.

Cost from the Green Bean Perspective

From a cost perspective, the price of these Hambela XS green beans is 139 RMB per kilogram, and the defect rate is low enough to be negligible. The yield is about 90%, making it roughly 155 RMB per kilogram of roasted coffee. In shops selling roasted beans, this variety of Hambela typically sells for anywhere between 27 and 36 RMB per 100g. Meanwhile, 15g of Hambela beans made into a pour-over coffee in a physical café would sell for about 20 to 35 RMB. Of course, after accounting for the costs of opening a shop and operations—especially for offline brick-and-mortar stores—the overall profit margin on coffee remains quite low.

Returning to home roasting, the cost advantage isn’t actually that significant. Even with such a basic roasting machine, you’d have to drink over a thousand cups of coffee to break even. The main point, naturally, is that it’s good fun: you can control the process from green bean to roasted bean and experiment with how different roasting methods affect the flavour.

The Downsides of Home Roasting

Regarding roasting itself: on one hand, the process isn’t exactly simple. You have to precisely control the temperature and airflow within a few minutes, making adjustments based on the actual situation, which ultimately reflects in the flavour profile. However, at the same time, the margin for error in roasting is actually larger than you might imagine. The batch above was roasted with completely manual control over the fan and heat; incorrect settings meant it took nearly ten minutes to slowly enter first crack, yet it still resulted in something “drinkable”.

Another significant issue is the green beans. Individuals buying green beans rely mainly on distributors who generally sell in 1kg bags. Smaller quantities exist, but the unit price is higher. This leads to the situation where if you roast a particular bean, you might be stuck drinking just that for the next month. Furthermore, for small-batch lots or more exclusive “specialty” beans brought back directly from the origin by “bean hunters”, you still have to buy roasted beans from others to taste them.

The Takeaway

For the vast majority of coffee enthusiasts, the money spent on a roasting machine would be enough to buy beans from various roasters for the next year, allowing you to drink coffee from all sorts of countries, regions, and varieties. This is arguably better than spending a month drinking your own various attempts at roasting the same Hambela.

However, life is about tinkering and fussing, isn’t it? Who knows, maybe one day I’ll go off and plant my own coffee tree?